by Cindy Schlosser

“Persons have the right to migrate to support themselves and their families. The Church recognizes that all the goods of the earth belong to all people. When persons cannot find employment in their country of origin to support themselves and their families, they have a right to find work elsewhere in order to survive. Sovereign nations should provide ways to accommodate this right.”

Strangers No Longer: Together on a Journey of Hope, United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2003

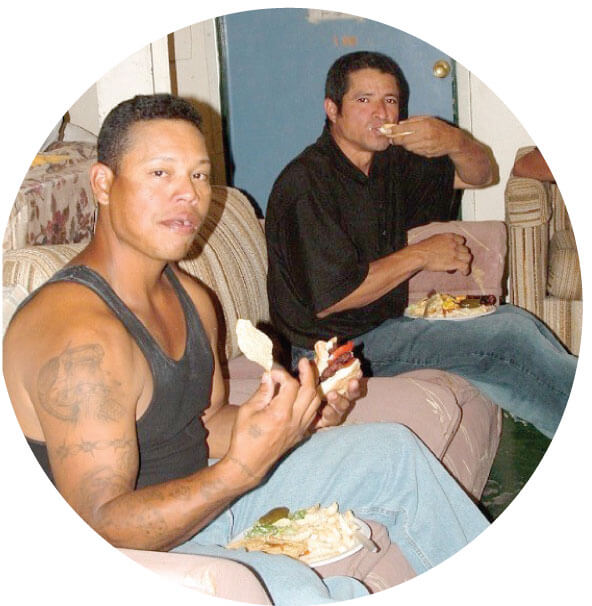

Manuel and I sat on an old, beat-up couch in the sala (living room). He had come home from a long day of roofing in the heat of an El Paso summer day.

“Cindy,” he asks, “why did you come here?”

Manuel is referring to Annunciation House, where we both live with about 30 other men, women, and children. It is our home and has been home for nearly 100,000 immigrants and refugees since its doors opened in 1978.

“I believe I have a responsibility as a U.S. citizen and a Catholic to care for those who are seeking work in order to provide a decent, humane life for their families and themselves,” I say.

I have volunteered for two years of service at Annunciation House. Manuel has come out of necessity to support his family.

“I make the journey from Nicaragua and stay a year to make enough money to give my children the things that only money can buy: food, clothing, and education,” Manuel explains. “Then, I return to Nicaragua for three months or until the money starts getting low.

“While I’m in Nicaragua, I stay at home and spend time with my children and my wife. I don’t look for work because there aren’t any jobs. I am a father and a husband. I have a responsibility to provide two basic necessities for my family — love and money to live. The situation in my country does not allow me to do that, so I have to search beyond our borders.

“I have made the journey from Nicaragua to the U.S. five times and have only been deported once,” Manuel continues.

“Why would you choose to go back to Nicaragua after making it here safely?” I ask.

Maria, a guest at Annunciation House, and Cindy.

Many children stay at Annunciation House.

I have learned at Annunciation House that some immigrants come to the United States to earn enough money to return to their families and open a restaurant or other family business in their home country. Others stay and send money (remittances) back to their families, understanding they may never see their families again.

“I have six children and my wife at home in Nicaragua,” Manuel continues. “I leave home and travel thousands of kilometers through Central America, Mexico, and the U.S. border to get here. Mexico is the worst.

“This last time, my brother-in-law and I walked three days through Chiapas (a state in the south of Mexico that borders Guatemala). We rode cargo trains and ran. I have seen people fall off the tops of trains, losing arms and legs. One man was sliced in half, right down the middle.”

Manuel runs his hand across his stomach to show me

“We immigrants are robbed and beaten by gangs, by the Mexican police, and security officials hired by the train companies. Many women have been raped.”

Casa del Migrante, a shelter for immigrants in Arriaga, Mexico, documents violence toward immigrants. A third of men and 40% of women fall victim to violence in the 160 miles between the Guatemala/Mexico border and Arriaga.

At the border between Mexico and the United States, immigrants again experience brutal treatment from the Border Patrol and civilian vigilante groups or in detention facilities.

I feel awe at the love Manuel has for his family. He risks his life for them. Familiar feelings of sadness and anger surface as they do each time I sit with a friend or stranger and listen to their stories of struggle for daily bread and a life of dignity. I feel frustration because our U.S. trade policies lead to the emigration of millions from Mexico and Central America.

As agricultural products flow back and forth among the countries, farming becomes a bigger business. People who have survived on small plots of land by raising food for their own livelihood get displaced.

I feel at home in Annunciation House, surrounded by men and women who share lives of both extreme poverty and of undying hope. During my two and a half years here, I have learned about immigration issues from books, seminars, meetings, and the Internet. But most importantly, I learned to listen to those whose voices are not heard.

I have heard fathers cry as they speak of the decision to leave their children. I have visited their children in their home countries, where they themselves cannot go and listened to their daughters and sons cry for them.

I have listened to mothers pour out their fears as well as their hopes for their children’s future. I have listened as teenagers vent the frustration of being the poor indocumentado, undocumented kid, who lives in a shelter.

“The poor are never invited to the table to discuss their own destiny,” says Ruben Garcia, the director of Annunciation House for the past 30 years. He teaches us to listen not out of pity but because our well being and that of the most marginalized, the poorest of the poor, are so deeply connected.

Sitting there with Manuel, I no longer try to explain my beliefs or philosophies. I simply listen. I witness to the truth of his experience and learn from his life of pain, hunger, fear, love, and hope.

I have learned to ask myself, “What am I doing to ensure that my neighbors’ voices are heard?”

“The human dignity and human rights of undocumented migrants should be respected. Regardless of their legal status, migrants, like all persons, possess inherent human dignity that should be respected. Often they are subject to punitive laws and harsh treatment from enforcement officers from both receiving and transit countries. Government policies that respect the basic human rights of the undocumented are necessary.”

Strangers No Longer

Border Mass

Some 500 Catholics from Mexico and the United States gather for Mass at the border fence on All Souls Day, November 2. Bishops from El Paso, Texas and Las Cruces, New Mexico celebrate Eucharist with the bishop of Juarez, Mexico. The Border Mass began in 1999.

All Souls is a day for remembering and praying for the dead, an important feast day in Hispanic culture. The gathering also celebrates life, work for justice, and the human dignity of immigrants. The Eucharist remembers the many immigrants who have died trying to cross the border and the many girls murdered and buried in mass graves in Juarez.

For Bishop Richardo Ramirez of Las Cruces the fence represents crimes, sins, and violence on both sides of the border for which we need forgiveness. In his homily he stresses that the physical barrier shouldn’t stop people on both sides of the border from loving each other “as the brothers and sisters they are in the eyes of God.”

At the sign of peace the fence prevents handshakes or embraces. The bishops and people press hands against the fence from both sides.