by Joan Mitchell, CSJ

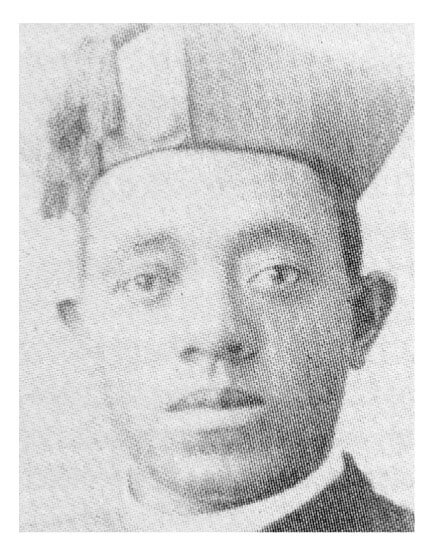

The baptismal record of the first full-blooded African American priest in the United States reads: A colored child born April 1, 1854, son of Peter Tolton and Martha Chisley, Property of Stephen Eliot. Augustus Tolton’s story begins in slavery and ends in early death, but reveals a courageous response to God’s call.

The Toltons were Catholic because the families who owned Martha Jane Chisley and Peter Paul Tolton were Catholic and had their slaves instructed and baptized.

When the Civil War began, Peter Tolton escaped from slavery to join the army. Before her children could be sold away from her, Martha slipped away with Charles, nine; Augustus, eight; and Anne, not quite two. They left their owner’s farm in Ralls County, Missouri, and walked toward the Mississippi River and the free state of Illinois on the other side.

In Hannibal, Missouri, slavehunters recognized and tried to capture the Toltons. Federal soldiers rescued them and pointed them towards the Mississippi. There Martha found an old rowboat and rowed her family across the Mississippi with slavehunters firing at her from the shore. When they reached the Illinois shore, sympathetic people showed them the road to Quincy where they found a welcoming African American community.

Martha, Charles, and Augustus got jobs in a Quincy tobacco factory. They worked from eight until six, six days a week, in the midst of nicotine fumes, for the nine-month season. Mrs. Tolton took the children to Mass at St. Boniface Church, a 2,000 member German parish, where African American Catholics felt welcome.

Mrs. Tolton learned through the long lists of Civil War dead that her husband had died in St. Louis. In 1865, Charles died of pneumonia. Mrs. Tolton, with the support of Father Schaeffermeyer, the pastor of St. Boniface, enrolled Augustus, now 11, in the parish school during the three months the tobacco factory was closed. But white parishioners objected and some children treated him cruelly. Finally Augustus withdrew.

Mrs. Tolton decided to attend Mass at St. Peter’s Church, so the family would not cause Father Schaeffermeyer any more trouble. The Irish priest there, Father Peter McGirr, quickly enrolled Augustus in the parish school and taught him to be an altar boy. For the next five years Augustus served early Mass, worked at the tobacco factory, and attended St. Peter’s school in the off months.

Augustus completed St. Peter’s in 1872, at age eighteen, and was confirmed. That was the moment when he asked his two priest friends, Father Schaeffermeyer and Father McGirr, a question he had long had himself. Did they think he could ever become a priest? Both priests knew what a good Catholic and intelligent young man Augustus was, so they both said, “Why not?”

When the two priests tried to help Augustus find a seminary at which to study, they realized he needed more formal education. So Augustus went back to the tobacco factory, this time making cigars at nine dollars a week, and studied evenings with the new assistant pastor at St. Boniface, who tutored him and two white boys. But even with the proper academic qualifications, Augustus could find no seminary or religious community that accepted African American candidates. His letters of applications were ignored or returned with a “No Blacks accepted” reply.

Augustus ministered among African American people before he became a priest. He helped the new pastor at St. Boniface, Father John Janssen, start a school for the African American children of Quincy. He did the work of a social worker or street priest today. He rounded up stray kids to come to his school, visited children’s families, and invited African American Catholics who had drifted away from the Church back in.

In 1879, when he was twenty-five, Augustus was accepted to one of the finest seminaries in the world — the Pontifical College of Sacred Propaganda in Rome, a seminary for training missionary priests. Augustus’s seven years of perseverance paid off. He left for Rome expecting to become a missionary in Africa, but at the end of five years, when Augustus was ordained, his teachers decided African Americans needed priests and assigned Father Tolton to his hometown of Quincy.

Reluctant to return where he had been a slave and where no seminary or religious community had wanted him, Augustus had nonetheless promised to go where the Pontifical College sent him.

A delegation of African American and whites headed by Mrs. Tolton and Anne met Augustus’s train at the Quincy station and ushered him into a flower-draped carriage. A brass band marched before it, playing “Holy God, We Praise Thy Name.” People streamed into St. Peter’s, the church where Augustus had received First Communion and Confirmation, to receive the first blessing of their new priest.

Augustus’s adult troubles began where his childhood troubles left off. Protestant ministers, who had churches for African Americans in Quincy, feared this priest from Rome would lure their members to the Catholic faith. A new pastor at St. Boniface came to resent Augustus because too many white parishioners went to hear him preach and put their money in his collection basket. Augustus heard the sneer “nigger priest” from a fellow priest and finally asked to move to Chicago, where he knew he was wanted.

Father Tolton became pastor for the Chicago Black Catholics in 1889; they numbered 30 members and met in the basement of St. Mary’s Church at Ninth and Wabash Streets. They called themselves the St. Augustus Society after the great African bishop. Soon 19 adult converts Father Tolton had made in Quincy joined him. The church moved into a storefront and grew to over 100 people.

When a woman donated $10,000 towards a new church for the African American Catholic community, they purchased a lot at 35th and Dearborn. Mother Katharine Drexel, foundress of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament, helped financially, too. The community hired an African American architect, African American contractor, and African American workers to build St. Monica’s Church, named after the mother of St. Augustus.

As St. Monica’s parish grew to over 600 African American Catholics from all over the city of Chicago, Father Tolton worked hardest at what he believed in most—education, adult instruction, and works of mercy. He made daily rounds through his parish, preached wonderful sermons, and passed on his excellent education. He often found it discouraging trying to help people spiritually who had so many material worries.

Augustus died suddenly on July 4, 1897 from heat exhaustion. His hard life as a boy slave, as a worker in the tobacco factory, and the many disappointments he suffered as a priest had worn him out. He had served as a priest for 12 years.

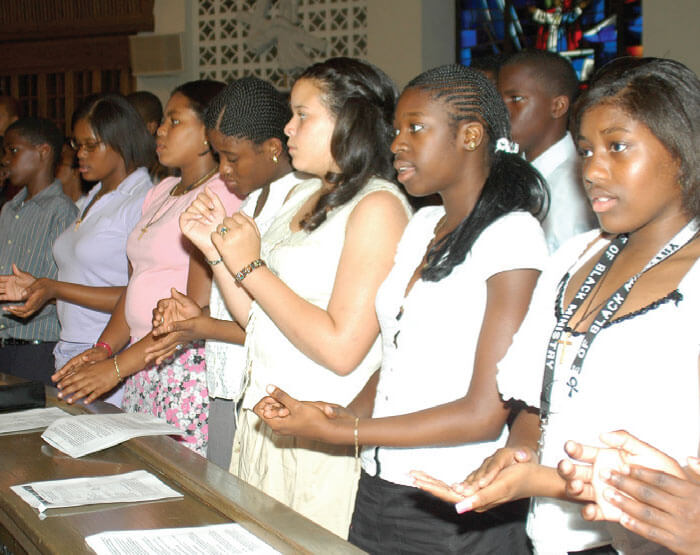

Father Tolton was buried where he asked to be — in the priests’ lot in the St. Peter’s cemetery in Quincy, but later another priest was buried on top of his grave. Tolton’s name appeared only on the back of the gravemarker. This pioneer African American priest experienced racial prejudice in life and in death. Today many other African American men have responded to God’s call to become priests. At present there are 16 living African American bishops in the United States, 9 of whom remain active.

When have I experienced prejudice against me? When have I experienced privilege I didn’t earn

Check the statements below that are true for you.

- My neighbors accept me.

- I go shopping without being followed or harassed.

- My history textbook includes what people like me have contributed to our country.

- I am never asked to speak for the people of my race, gender, or religion.

- I wish more people in my class looked like me.

- My family can live wherever we want.

- I don’t have to worry about police stopping me unless I’m speeding.

- People cross the street when they see me coming.

- I can buy make up and bandages the color of my skin.