Father G-dog, or G for short, is Jesuit priest Greg Boyle. He is Executive Director of Homeboy Industries in Los Angeles, a program that gives gang members hope for a life. Dog is gang slang for best friend.

“A great many kids in my neighborhood don’t plan their futures; they plan their funerals,” says Father Greg. “They ask me to do them and plan the songs to sing.”

From 1986 to 1992, Father Greg was pastor of Dolores Mission, the poorest parish in the Los Angeles Archdiocese. The small, stuccoed church with a red tile roof sits on a corner in the largest public housing development west of the Mississippi. For the neighborhood, it’s a corner of hope. The church houses a shelter for 65 people. Children attend school across the street.

Dolores Mission is in the 16-square-mile, Hollenbeck Police Precinct, which has 36 criminal gangs and 6,400 gang members. “LA is the gang capital of the world,” explains Father Greg. “This little corner, this little postage stamp square on the map, is the gang capital of LA.”

Father Greg created “Jobs For A Future” in 1988 to develop positive alternatives — an elementary school, a day care program, and finding legitimate employment for young people.

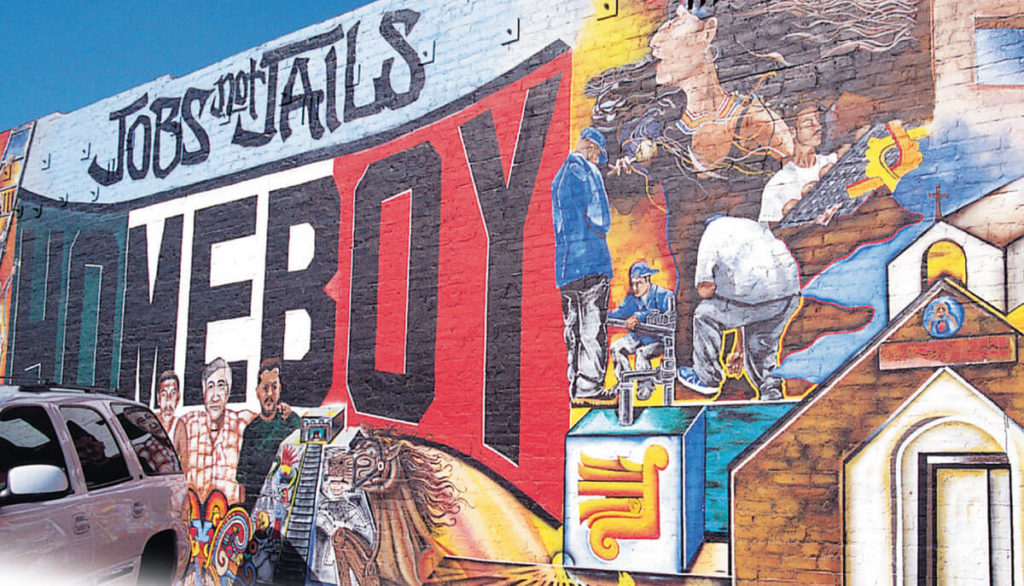

In 1992, Father Greg launched the first business, Homeboy Bakery. It provided training, work experience, and above all, the opportunity for rival gang members to work side by side. The success of the bakery led to additional businesses. Homeboy Industries became an independent non-profit organization in 2001. Today its enterprises include Homeboy Bakery, Homeboy Silkscreen, Homeboy Maintenance, Homeboy/Homegirl Merchandise, and Homegirl Café.

“We have 250 to 300 employees, all of them from different gangs, half of them enemies,” explains Father Greg.

Homeboy Industries has new headquarters in downtown Los Angeles. The move downtown — two blocks from Union Station in gang neutral territory — has opened services up to all of LA County. “Homeboy serves as a beacon of hope for those seeking to leave gang life, for whom the barriers and challenges are great, and for whom there is virtually no other avenue to enter the mainstream,” says Father Greg.

Father Greg wants to translate the word blessed that begins each of the beatitudes a new way. The usual beatitudes say, “Blessed are the single-hearted. Blessed are the merciful. Blessed are those who struggle for justice.” Father Greg reflects, “Scholars tell us it is closer to the original language to say, ‘You’re in the right place if you are single-hearted. You’re in the right place if you struggle and work for justice. You’re in the right place if they persecute you and if they hate you, if they speak ill of you.’

“The beatitudes tell us where we need to be. To stand with those who are at the margin, who have had their dignity denied — that is the place of the passion and joy. That is where Jesus is.”

Father Greg sees his work as telling young people the truth about who they are. “These youth have distorted images of themselves, so we hold up a mirror. Here’s who you are. You’re exactly who God made you to be.

“This is like the kid who told me not to worry about getting gas even though my gauge said E.

‘What do you think E means?’ I asked him.

“‘Enough,’ he says.

“‘What do you think F means?’

“‘Finished,’ he says.

“The kids who come to my office look in the mirror and see empty. It is our communal task to tell them, ‘You have goodness, gifts, and talents. You are enough. You are who God wants you to be.’”

Moreno returns from probation camp and shows me his transcript. “Straight A’s,” he says. I open his transcript; I see two B’s, two C’s, and one A; I think, “Close enough.” I say to him, “If you were my son, I would be the proudest man alive.” He moves his fingers to his eyes to stop tears.

I realize his mother is a crack addict who has disappeared. His father is in state prison and will never leave prison alive. His grandmother, who is raising him, is a good woman but not effective. I buried his very best friend a month earlier; he was killed in our streets.

“I bet you are afraid to be out, aren’t you?” My question presses the play button on his tear ducts, and he dissolves in tears. “It’s going to be OK,” I say.

He wipes away his tears and with defiance says, “I just want to have a life!”

I said, “Who told you you would never have one? In all those letters from camp you wrote about all the things you learned about yourself. The gifts and talents you didn’t know you had. At the moment you think you are in a deep dark hole, but the truth is you are in a tunnel. If you keep walking, the light is going to show up. I can see it; I’m taller than you are. And after all, (I hand him back his transcripts) straight A’s.”

Father G joins in giving young people the message they don’t hear. “It is our collective task,” he says, “to hold the mirror up to each other, but especially to those on the margins whose dignity has been denied, who are voiceless, whose burdens and needs are more than they can bear.”

A graffiti-removal crew cruises East 19th in front of both the Precinct Police Station and Jobs for a Future. High-powered spray washes graffiti off trees and sidewalks. A coat of paint cleans the graffiti off the walls of an underpass.

Father Greg thinks gang violence is a symptom. “It is the cough that indicates you are allergic to your cat,” he says. “Gang violence points beyond itself to poverty, to families that don’t function because of despair, unemployment, and racism. Gang violence tells us that we haven’t dealt with access to education, to medical care, to opportunities in general.”

One day I was about to say Mass. I saw police officers patting down three little gang members. They didn’t find anything. One officer took this huge wad of gum out of his mouth and put it in the tiniest kid’s hair, a kid named Ernie. Then he took the baseball cap that had been thrown on the ground and smooshed it on Ernie’s head, rubbing the gum into his hair.

The next day I went to the Captain of the Police and asked him, “What do you think the police officer’s hope was in doing that to this kid?” The Captain said something to me that I’ve heard before, “Father, our strategy is a simple one. Make life as miserable as we possibly can for the gang member.”

I told him that is redundant in our community. Life is already miserable for the gang member. In fact, gangs are the places kids go when they have encountered their life as misery.

Those officers asked themselves, “What’s wrong with these three kids?” They thought they just aren’t scared enough. The truth is they are just not hopeful enough.

In Father Greg’s analysis, “Violence is the urban poor’s version of suicide, the way kids act out the self-destructive urge. If the problem is really despair, which I think it is, the solution is hope. Ask people who work with at-risk youth to call to mind their success stories. They will tell each kid had at least one loving, caring adult that paid attention. The surest antedote for the despair is the hope of one adult showing up.”