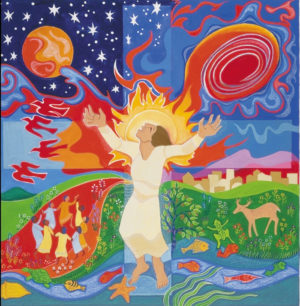

by Joan Mitchell, CSJ

Outside St. Paul High School it’s dark at six thirty in the morning in December. Inside this school in Santa Fe Springs, California, more than 550 students gather for Eucharist with Bishop Alex Salazar. It’s Advent and time to walk the streets of Los Angeles to raise money for the Los Angeles Catholic Worker Soup Kitchen.

“You are one body, one Spirit in Christ,” the bishop says. “You will make an impact. You are here because you believe all people have basic human rights — the right to eat, to be clothed, to have shelter because each of us is truly a child of God.”

Bishop Alex closes Mass by asking students, parents, and alumni to take off their shoes. Everyone looks bewildered. He then asks everyone to hold the shoes up in the air. He proceeds with a blessing, saying, “Bless these shoes and those who are wearing them as they walk for those who go hungry. May they have strength to walk the 26-mile route.”

Bishop Alex Salazar blessing the shoes of all those walking.

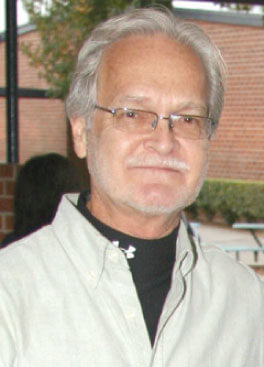

Dan Jiru

Students in the gym during Mass.

Students and alumni climb on buses for the ride north and step out into Salazar Park, East Los Angelos, and stream up the sidewalk — a river of gray sweatshirts and blue jeans. The March for Hunger begins.

Retired religion teacher Dan Jiru started this march in 1972. He and a few students from his religion classes made the first walk, circling around the school block. Mr. Jiru inspired social responsibility in St. Paul students for almost 30 years. He died two a half weeks after the 39th March on December 4, 2011.

Today students walk 26 miles and give the Catholic Worker its largest single donation. Nearly 900 students, alumni, parents, and friends participate.

The March for Hunger starts in East Los Angeles, follows Chavez Avenue to the Mexican market on Olvera, moves north through Chinatown, and turns west on Sunset Boulevard all the way to the beach in Santa Monica.

The walk is fun. Students have all day to complete it. A guy gives his girlfriend a piggyback ride but not far. Roses bloom on green lawns. Yellow acacia blooms hang from trees. Students walk the sunny side of the street in the cool morning and the shady side in the warm afternoon.

At McDonald’s many stop for breakfast, bathroom breaks, and chats with friends. Others line up for bakery sweets. A lamppost ad warns against obesity.

Midmorning two seniors carrying pizza stop to take off their sweatshirts. They explain the pizzas are for homeless people they know they will see along the way.

On the sides of building and the walls behind the cash registers inside businesses are paintings of Our Lady of Guadalupe.

A man in an SUV turns a corner and asks two students what they are doing.

“A walk for hunger,” they reply.

“Cool,” he says and drives on.

A homeless man sits on the sidewalk eating pizza. The two seniors have walked by.

Every walker has a story.

“I walked all four years all 26 miles.”

“I only made 20 that year in the rain.”

“My mom went to St. Paul’s and did the walk; now I’m doing it.”

At the Olvera Market, friends eat, hang out, and give their feet a rest after six and a half miles. A mariachi band plays in the street. Christmas decorations blow overhead.

Out on Sunset Boulevard below the Hollywood hills, students string out in bunches of friends. Their white t-shirts identify them. BMWs, Lincoln Navigators, and Mercedes speed by.

Jackie and her group of friends pause at a corner. “Our teachers explained the walk to us our first year in school,” she says. “We know what we are walking for. We pay $55 to take this walk.” Jackie is the first generation in her family to go to school in the U.S. and to think about going to college. “My mother is Mexican, and my dad Bolivian. I’ve seen my mom donate a lot to our parish as I grew up, which made me want to do the walk.”

The sun is sinking on Sunset Boulevard. Two Rolls Royces pull out of Starbucks.

In Beverly Hills mansions appear on both sides of wide streets, many with high well-trimmed hedges to hide them and gates to keep people out. Lavish lawns invite a quick sitdown. Flowers cascade along walks. Students met Wynonna Judd out for a walk one year.

At Whittier the walk turns south toward Wilshire Boulevard. Huge sycamore trees overhead make the streets look elegant. Four girls sit on a curb waiting for friends to catch up. Students never walk alone but always in groups. Making new friends is part of the walk. At 4:45, December dark is falling and students wearing shorts put their hoodies up and caps on for the final miles.

The Hunger Walk is both a spiritual pilgrimage and a very physical experience. Step after step, students slowly internalize what it is like to be homeless and wandering the streets on punishing sidewalks.

At the beach in Santa Monica, homeless folks with their belongings in shopping carts are bedding down for the night. Only an orange glow remains where the ocean meets the sky. The shore wind is vigorous, the grass soft.

Sophomore boys from Don Bosco High School are sitting on the grass at the beach, the first to arrive there about 4:45. “My feet are seriously killing me,” says Victor, who finished two hours earlier than last year. “I have been working out. I wanted to do a little better than last year.”

“I just came to the United States and I didn’t know there were poor people here,” says senior Jun Cho. “Doing this march helps people who are going through a hard time right now.”

Jamie Lizada feels like he got a reality check. “I saw disabled people alone, crazy people seeking help, and hungry people begging for food,” he says. “Where I live everyone is well-to-do, but on the walk my eyes were opened to how life really is for those living in poverty.”

Hector Palencia is a graduate of St. Paul High School, who teaches religion at Don Bosco Tech. He has interested more than 100 students in making the walk. “If you talk to any St. Paul alum,” says Hector, “you will hear the walk made a difference to them. I made the walk even after I was out of school.”

Kristin Matuz, another alum and science teacher, is loading students on buses to return to St. Paul’s. “Ours is the first family to have three generations do the walk,” she says. “You may start out with a group of friends and by the end be with a whole new group. The pain is worth it. It’s amazing what we have done for the soup kitchen.”

Back at the high school parents grill hot dogs and set out a meal for hungry walkers as they limp off the buses.

“Socially conscious students are struck by seeing the poverty and degree of homelessness,” says Sister Beatrice, a religion teacher. “As they keep going and get more tired, they see increasing wealth and experience less accessibility to bathrooms. The longer part of the walk is in richer neighborhoods, which represent the smallest part of our population.”

“Not many people can say they have walked 26 miles for someone other than themselves, but I can,” says Dolores Arias. “It’s all about being thankful for what you have and realizing what’s going on outside of your own little bubble.”

“Just because the homeless don’t have as much stuff as we do doesn’t make them less human,” says Nicole Morales. “I have so many blisters on my feet, but every blister is worth it. A few days of pain is worth making a difference in someone’s life.”

“I feel the walk made me a better person,” says sophomore Robert Vargas. “I was part of something that helped some of those unfortunate people realize there was hope. It made me realize how lucky I am to eat good meals every day. I know that if I wasn’t fortunate, I would look for help and support from others.”