by Nicholas D. Kristof & Sheryl WuDunn

Srey Rath is a self-confident Cambodian teenager whose black hair tumbles over a round, light brown face. She is in a crowded street market, standing beside a pushcart and telling her story calmly, with detachment.

When Rath was fifteen, her family ran out of money, so she decided to go work as a dishwasher in Thailand for two months to help pay the bills. Her parents worried about her safety, but they were reassured when Rath arranged to travel with four friends who had been promised jobs in the same Thai restaurant. The job agent took the girls deep into Thailand and then handed them to gangsters who took them to Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Malaysia. Thugs sequestered Rath and the other girls inside a karaoke lounge that operated as a brothel. One gangster known as “the boss” explained that he had paid money for them and that they would now be obliged to pay him.

Rath was shattered when what was happening dawned on her. The boss locked her up with a customer, who tried to force her to have sex with him. She fought back, enraging the customer. “So the boss got angry and hit me in the face, first with one hand and then with the other,” she remembers, telling her story with simple resignation. “The mark stayed on my face for two weeks.” Then the boss and the other gangsters raped her and beat her with their fists.

The girls were forced to work in the brothel seven days a week, fifteen hours a day. They were kept naked to make it more difficult for them to run away or to keep tips or other money. The girls were never allowed out on the street or paid a penny for their work.

“They just gave us food to eat, but they didn’t give us much because customers didn’t like fat girls,” Rath says. The girls were bused, under guard, back and forth between the brothel and a tenth-floor apartment. The door of the apartment was locked from the outside. One night, some of the girls went out onto their balcony and pried loose a long, five-inch wide board from a rack used for drying clothes. They balanced it between their balcony and one on the next building, twelve feet away. The board wobbled badly, but Rath was desperate, so she sat astride the board and inched across.

“I was scared,” she says. “But I was even more scared to stay. We thought that even if we died, it would be better than staying behind. If we stayed, we would die as well.”

Once on the far balcony, the girls pounded on the window and woke up the surprised tenant who let them out the front door. They found a police station and stepped inside. The police first tried to shoo them away, then arrested the girls for illegal immigration. Rath served a year in prison and then she was supposed to be allowed to go back to her own country. She thought a Malaysian policeman was escorting her home when he drove her to the Thai border — but then he sold her to a trafficker, who peddled her to a Thai brothel.

Rath’s saga offers a glimpse of the brutality inflicted routinely on women and girls in much of the world, a problem that is slowly gaining recognition as one of the paramount human rights problems of this century.

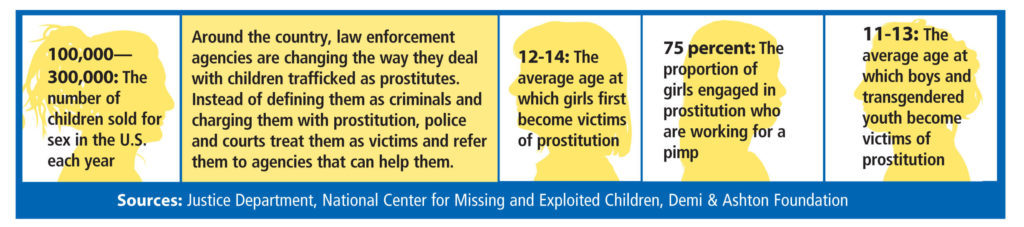

Amartya Sen, the Nobel Prize winning economist, has developed a measurement of gender inequality that is a striking reminder of the stakes involved. “More than 100 million women are missing,” Sen wrote in a classic essay in 1990, spurring a new field of research. Sen noted that in normal circumstances women live longer than men, and so there are more females than males in much of the world. Even poor regions like most of Latin America and much of Africa have more females than males. Yet in places where girls have a deeply unequal status, they vanish.

Discrimination in wealthy countries is often a matter of unequal pay or underfunded sports teams or unwanted touching from a boss. In contrast, in much of the world discrimination is lethal. In India, for example, mothers are less likely to take their daughters to be vaccinated than their sons — that alone counts for one fifth of India’s missing females — while studies have found that, on average, girls are brought to the hospital only when they are sicker than boys taken to the hospital. All told, girls in India from one to five years of age are 50 percent more likely to die than boys the same age. The best estimate is that a little Indian girl dies from discrimination every four minutes.

The global statistics on the abuse of girls are numbing. It appears that more girls have been killed in the last fifty years, precisely because they were girls, than men were killed in all the battles of the twentieth century. More girls are killed in this routine “gendercide” in any one decade than people were slaughtered in all the genocides of the twentieth century.

In the nineteenth century the central moral challenge was slavery. In the twentieth century, it was the battle against totalitarianism. We believe that in this century the biggest moral challenge will be the struggle for gender equality around the world.

The owners of the Thai brothel to which Rath was sold did not beat her and did not constantly guard her. Two months later, she was able to escape and make her way back to Cambodia.

Upon her return, Rath met a social worker who put her in touch with an aid group that helps girls who have been trafficked start new lives. The group used $400 in funds to buy a small cart and a starter selection of goods so that Rath could become a street peddler. Rath outfitted her cart with shirts and hats, costume jewelry, pens and small toys. Now her good looks and outgoing personality began to work in her favor, turning her into an effective saleswoman. She saved and invested in new merchandise, her business thrived, and she was able to support her parents and two younger sisters. She married and had a son, and began saving for his education.

Rath’s eventual triumph is a reminder that if girls get a chance, in the form of an education or a microloan, they can be more than baubles or slaves; many of them can run businesses. Many of these stories are wrenching, but keep in mind this central truth: Women aren’t the problem but the solution.