by Joan Mitchell

“What I eat is a material question,” says David Beckmann. “What my neighbor eats is a spiritual question. Our spiritual survival depends on responding to the least among us.”

Beckmann is a Lutheran minister but has no congregation. He is an economist but no longer works for the World Bank. Instead as president of Bread for the World, Beckmann lobbies members of the, U.S. Congress to pass legislation to feed people who are hungry both at home and around the globe.

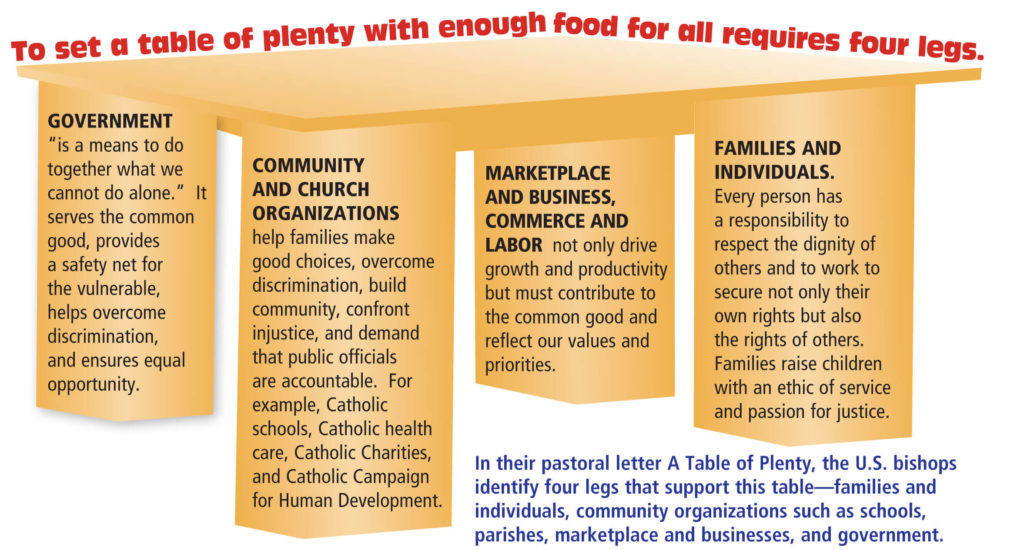

Bread for the World draws individuals and congregations into its work of lobbying for legislation to reduce hunger. “Churches, synagogues, and mosques do great work with food shelves and Thanksgiving baskets but they can’t feed the hungry alone,” says Beckmann. “All the charitable feeding programs amount to only 6% of the food the poor receive through government nutrition programs.”

Bread for the World specializes in the work of advocacy. “When I talk in parishes,” says Beckmann, “I tell people that every time they bring a can of food for the food shelf or work in a feeding program, they should also write to their legislators. Do both. Feeding the hungry requires both charity and advocacy.”

Congregations and parishes that belong to Bread for the World send offerings of letters to representatives in Congress to give voice to the needs of people who are poor. “Our Christian faith gives us a habit of hopefulness,” says Beckmann.

Bread for the World has helped parishes and congregations work to achieve the United Nations’ first Millennium Development Goal — to cut in half the number of people living in extreme poverty and hunger by 2015. The nations of the world met the goal five years early. Globally 836 million people still live in extreme poverty. Ending extreme poverty by 2030 is the number one United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal. About one in five persons in developing regions lives on less than $1.25 per day, especially in Southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Wars and the pandemic work against the goal.

Beckmann became a pastor before he became an economist. “I believe God is moving in our history. The faith-filled advocates for the hungry and poor of our world have a chance to bend history and lead an exodus from hunger.”

Why does Beckmann see an exodus from hunger? True, with the recession more people in the U.S. live below the poverty line today than in 1976. True, no president has made ending poverty in the world one of his top 20 priorities.

Also true, says Beckmann, “We know the greatest return on investment is early childhood education. We reformed the use of food stamps in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) by giving people debit cards that makes tracking how benefits are spent easy. We know the effects of malnutrition in the first 1,000 days of life damages children’s mental capacities and leaves them dependent, unable get out of poverty. We have ready-to-use therapeutic food that can change that.”

In lobbying the members of Congress, Beckmann often sees children’s drawings and letters framed or posted in their offices. In one church teens led the adults. “The adults felt reluctant to do an offering of letters,” Beckman recalls. “A high school youth group studied hunger issues, introduced the issues to the congregation, and then asked people to stop at a booth on the way out of church and write a letter. Now the whole church writes letters every year.”

Beckmann values Catholic social teaching. “It is a great gift to the rest of Christianity,” he says. “The consistent, authoritative teaching over decades gives continuity.”

How did Beckmann become a pastor, economist, advocate to end hunger? “I was baptized in H20 and bathed in God’s love in my family,” says Beckmann. “Experiencing the love and forgiveness of God in Jesus was built into my personality in the way I was raised. I’m terribly grateful for that.

“My mom and dad were conservative, small town Nebraska kids who knew the Lord and were trying to do what the Lord wants. Their faith and commitment affected my four sisters and me.

“As a girl my mom had to leave home because her parents couldn’t feed her. She was the oldest girl. She left the farm and became a companion and household helper for a lady in Lincoln, Nebraska. With her first wages she bought furniture for the family back home. Through the years she taught a lot of women to sew clothes for their families, but in helping people in need, she never had any sense of reaching down because she had been there.

“My parents believed in education. My dad got a Ph.D. People’s rights really mattered to him. He was active in an organization of the Lutheran Church that worked on race issues and racial tolerance. He took me to civil rights meetings.

“My parents invited a man named John Samuel from India to our home. He was studying to be a teacher with my dad and became part of our family for a year. We invited him to our church, but because of his dark skin, people wondered why we had brought a colored man into our church.

“I arrived from Nebraska at Yale with corn coming out of my ears,” Beckmann remembers of his college days. “I showed up in the middle of the antiwar and black power movements in the 60s. Stokley Carmichael came to Yale and spoke to a mix of black and white students. ‘Don’t come to our neighborhood to fix the problem.’ he said. ‘The problem is in your neighborhood, too. Go to your neighborhood to fix the problem.’”

When he graduated in the late 1960s, Beckmann received a fellowship and an airline ticket. He quickly realized that he could just as cheaply fly around the world to get to his job in Ghana as fly directly there and back. “I found student activism everywhere and learned what was going on in the world. Being in developing countries as a young person is important.”

Beckmann went to the seminary of the church in which he grew up — the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod. When he finished, the congregation in which Beckmann served as a student pastor ordained him as a missionary economist, not a traditional pastor. Beckmann then studied at the London School of Economics and worked for the World Bank.

Twenty years ago Beckmann moved from economics to hunger advocacy. “I took a two-thirds pay cut when I came to Bread for the World. It made me realize I really feel called to this work. But I also feel inadequate. I love the gospel passage that faith the size of a mustard seed can move mountains. God wakes me up every morning and says, ‘You’re David, you could be better but here’s the job.’ As Mother Teresa says, ‘Do what’s in front of you.’”