by Ed Fasterly

A piece of notebook paper lay in my mailbox in the camp counselors’ lounge. Scrawled across the page was the message:

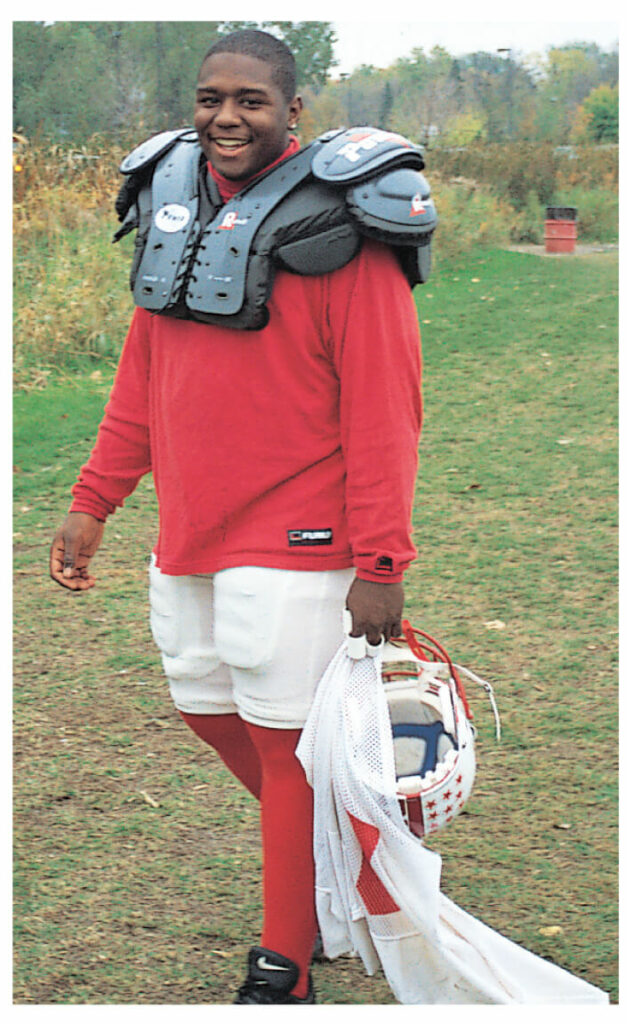

I headed over to his cabin. I had heard from the other younger counselors that Eli was a college junior. That was a little intimidating, but beyond that Eli was physically intimidating—a football player over six feet tall and a solid mass of linebacker muscle. I am five foot eight and three years younger.

I knocked on the door of his cabin.

A booming voice said, “Come in.”

I walked in. Eli was huge, even sitting on his cot.

“What’s up?” he asked.

“I got your note.”

“I heard you write poetry,” he said, putting down his pen and notebook.

The pen led my eye to drawings, sketches, paintings, and collages on his walls, each one impressive and all of them with the name “Elias” in the bottom corner.

“I write poetry and songs. Do you?”

“I’m trying,” he began. “I draw. I have been drawing for as long as I can remember. It’s my way of expressing the way I see the world around me.” He paused. “Lately I’ve been reading poetry. I think that some of my thoughts can only take form in words, you know.”

I looked up at an ink drawing of a man with corn rows in his hair holding up the world. “Sometimes I’ve wanted to draw when I’m stuck on words.”

That’s how we started talking and kept talking and talking. We both grew up in the city; both did music. I played guitar and he flowed with a hip-hop group.

“Hip hop is poetry, isn’t it?” I said, “A song without music is a poem. When you’re rapping, you’re flowing. When you’re reading your poetry out loud, you’re flowing.”

“My rhymes only go with music,” Eli insisted. “But my girlfriend said the same thing. I read her one of my rhymes without the music. She said, ‘You should make that spoken word.’ I tried to explain that if the music wasn’t there, it wouldn’t mean the same thing.”

“Yeah.”

Eli dug in a backpack and handed me a notebook opened to a page in the middle. “Tell me what you think of this poem, but not now, man. I can’t deal with that, people reading my stuff in front of me.” Eli smiled.

“I’ll give it back at lunch?”

“Yeah.”

On the walk back to my cabin I opened up to the page I held with my finger.

The poem punched me with pain I didn’t know. At lunch I asked Eli when he had written it.

“Last summer when I was living at my mom’s house,” said Eli. “This homeless crackhead walked up and down our street, preaching and always talking about the Great Silence. Then he’d drift off into some other place of mind. I didn’t understand what he was saying until these thug punks one day just up and shot him. BANG!” Eli made a gun out of his hand. “Like that. My mom, my little brother and sisters, and everyone in our neighborhood walked out and stared at him, lying there on the street. Nobody said a word. That’s when I figured out what that crackhead meant.”

“It’s a great poem.”

“That’s the one I’m most proud of,” he said, cutting me off, “the other ones are crap.”

“Somehow I doubt that,” I said.

“Read them,” he said laughing, “some of them redefine ‘crap’.”

I knew exactly what he meant, and I laughed, too.

A couple of weeks after camp Eli picked me up at home. He had a car.

“What’s up?” he asked. “You got your stuff?”

I nodded and held up my notebook, “You?”

“Yeah,” he said, “it’s in the car. Where’re we headed?”

“What about Uptown?” I said. “I hang out at a coffee shop there. What kind of music you got?”

“What do you want to hear?” Eli asked.

“Whatever.”

Eli turned up the music on the car stereo and a smooth, hip-hop beat saturated the car with bass and rim shots and a man flowing about lost souls.

“You writing at all?” I asked.

“Trying,” he said. “My ma has me painting the house and cleaning up the yard. Football started last Monday. When I’m done with all of it, I’m too tired to think, let alone write.”

“I hear that,” I said. “I’m working every day at my dad’s office to make a little money before school starts.”

I walked in the coffee shop door first. It was cluttered and artsy in the stereotypical, coffee-shop way. The girl behind the counter had dreadlocks and the clientele was mostly late teen and college-age folks. I was a regular. I saw several faces familiar enough to make eye contact and nod hello. Today they shot puzzled stares in my direction. Folks stopped talking or playing chess, looked up, turned around, and murmured to each other.

As I got to the counter, I heard Eli say quietly, “These people don’t want me in here. This isn’t a place for black folks, man.”

I looked at Eli. I saw what the people of the cafe were seeing—not a football player, a fellow counselor, or an artist, not a big guy wearing a white T-shirt, jeans, and boots. Eli was black. I was white, just like everyone else in the coffee shop—the patrons, servers, probably the artists whose works hung on the walls. I felt sick.

“You want to sit outside?” Eli asked. “This crowd is lame.”

Outside in the late summer sunlight Eli leaned over his coffee. “I don’t get people around here, this city, everywhere.” He looked up at me. “My whole life people have been doing this shit to me. It’s not like you get used to it. It’s like you just start to expect it. I’m 20 years old, and I’m in college. Do you think they see me as a student of higher learning or a future art teacher? Naw, they don’t see that.

“It’s like there’s two of me. There’s the me that I am—the me that I see when I look in the mirror, when I write in my notebooks, and draw on the page, the me my family knows and my friends. Then there’s the me that the folks in there see: I’m a big, black, drug-dealing gangbanger that don’t have no right being in their precious, white coffee house. ‘What’s he doing in here? He should be out shooting other gangbangers and smoking crack.’ They don’t see the real me.

“It’s like Hollywood—TV, movies, MTV, and all the media you and I are drowned in every day turns the real me into this walking stereotype that everyone else sees. They don’t see a man walking in and ordering a drink. They don’t even see a man right away. They see black, then they see a man, and maybe if they got over themselves, they would see Eli.” His eyes seemed to drift off to someplace else as he sipped his coffee.

The door to the coffee house swung open as a patron left. Over the clink of cups against tables and bus tubs, the chatter of college students and artists, the drone of the college radio station, I heard a Great Silence.

TRUTH

this is for the prophets

of the streets

their clothing is dirty and torn

their testimony is a glock

in a sixth grader’s hand

exploding in violence

from the Great Silence

this is their sermon

this is for the prophets

of the streets