by Joan Mitchell, CSJ

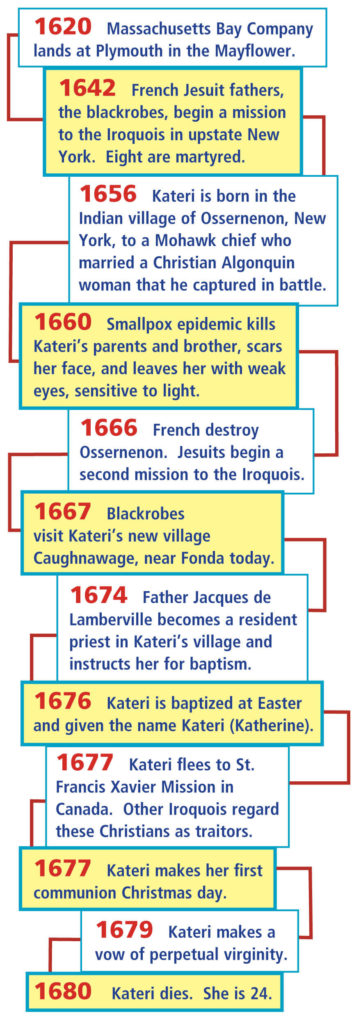

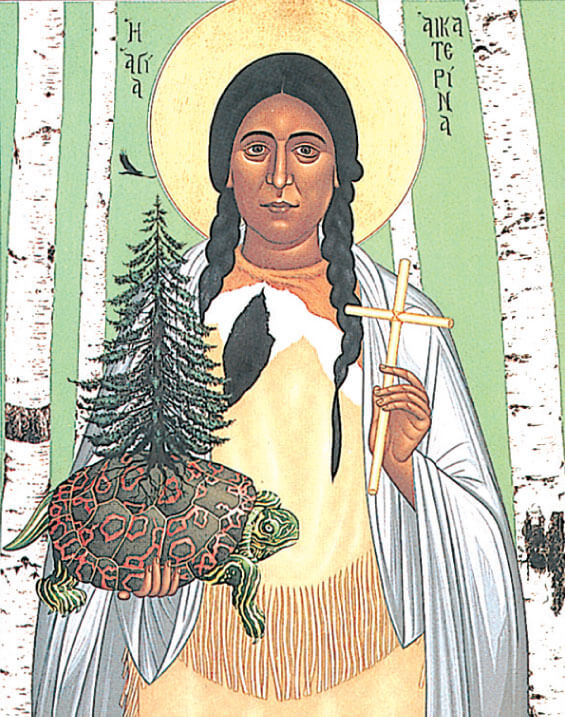

On October 21, 2012, the Catholic Church canonized the first Native American saint. Her own people, the Mohawks, the People of the Longhouse, called the new saint many names. Her family called her Tekakwitha, She Who Moves Slowly, probably because of her poor vision. Kateri, or Katherine, is the name she received at Baptism.

After her baptism people in her village called her the Christian, which also meant the traitor. Most people in her Turtle clan hated the French who brought Christianity among them and also fought them and destroyed their villages. Today the Church recognizes Kateri is a saint, the Lily of the Mohawks, the first Native American to make a perpetual vow of virginity.

Kateri’s mother was a Christian from the Algonquin tribes. Her father was a Mohawk chief who captured her mother during war and married her. They had two children, a boy and a girl.

The Mohawks or Iroquois are among five Native American nations that formed a confederacy to stop wars among them. The original 13 colonies modeled their first confederacy on the Iroquois plan. Among the Iroquois all votes had to be unanimous. This made persuasion the key to governing. The longhouse with room for many symbolized their value on community and participating in decision making. Land and hunting rights belonged to all the nations.

Spiritually the Iroquois were also known for their fearless courage and contempt for pain and suffering. Composure in battle or torture demonstrated spirit power. They lived in gratitude for the powers of life in the world, for animals they hunted, for the corn, squash, and beans they cultivated.

French fur traders traveled up the rivers and into the woods of Canada and New York to do business with the Native Peoples. Soldiers and priests followed. French Jesuit priests began their mission in New France in 1642; eight were promptly killed.

Kateri’s mother was a pious and faithful Christian who must have planted a desire for Christian faith in her daughter. Perhaps they prayed together or her mother told Kateri stories about Jesus. We have no record. What we know about Kateri comes from the journals of the Jesuit priests.

Smallpox killed Kateri’s parents and brother when she was only four. It scarred Kateri’s face and left her with poor eyesight. Her uncle took his niece into his longhouse. Like Kateri’s father, this uncle strongly opposed Christian religion.

In her uncle’s longhouse Kateri has to learn to work the land, cook, sew, dress meat, keep house, and do decorative bead and quill work. When she was eight, her family bound Tekakwitha to a boy they hoped she would get to know and eventually marry. But she refused. The family stopped treating her as a daughter and treated her as a captured slave.

In 1666 French soldiers destroyed the Iroquois village and forced the tribe to ask for peace and for missionaries. The next year three Jesuits came to the new village of Caughnawaga, where Tekakwitha lived with her uncle. The priests lodged in their longhouse and Tekakwitha had the work of serving them. Their piety impressed her.

A few years later priests established a Christian mission in the village, and different priests came when they could. Most of the Mohawks stayed very antagonistic toward the priests.

Father James de Lamberville became the resident priest in the village in 1674. About a year later he found Tekakwitha at home alone when he was visiting the sick. Everyone else was harvesting. She spontaneously revealed her desire to be a Christian.

Father de Lamberville accepted her as a catechumen and began teaching her. He found her to be “a natural Christian,” so he taught her during the winter of 1675-76 and baptized Tekakwitha at Easter, giving her the name Katharine (Kateri). She was 20.

Kateri did her household duties diligently, always willing to do her share of work. Once while she was making a wampum belt, a brave ran at her, yelling, “Christian, prepare to die.” She stayed composed and kept on working.

Father de Lamberville taught her ways to pray. Those in the village who opposed Christianity made fun of her prayer and her rest from work on Sundays and holy days. They threatened her and deprived her of food. They jeered her when she went to church; children sometimes threw stones.

Father de Lamberville suggested Kateri move to a Christian village. Her adopted sister and husband went, but her uncle refused to let Kateri go.

Later her sister’s husband came back when her uncle was away. Father de Lamberville wrote letters for Kateri to take to the mission. With her brother-in-law and another companion, Kateri trekked 200 miles through swamps and woods to the Mission of St. Francis Xavier at the Sault near Montreal.

Kateri loved the mission, worked at home and in the fields, and prayed constantly. An older Christian named Anastasia supervised the house, the work, the prayer. Anastasia knew Kateri’s mother and was related to her. They became friends. Kateri also made friends with a woman her age named Mary Theresa, who also valued prayer.

On Christmas in 1677, Kateri received Holy Eucharist for the first time. She centered her life around the Eucharist and Jesus’ cross. She wore a cross around her neck. Her faith in Jesus transformed the spirit power her tribe valued in battle and torture; Jesus’ passion and death redeemed others. Kateri identified with Jesus’ sufferings and imitated them. The priests often found her waiting when they opened the door to the mission church, sometimes barefoot in the snow, wanting to share Jesus’ sufferings. On Sundays she often spent the day in the mission church.

On her journey to the Christian mission Kateri had visited a convent of sisters in Montreal. Their life appealed to her. People said about Kateri, “She knows only two paths—the path to the fields and the path home and only two houses, her own and the church.” She wanted to lead a life of oneness with God through prayer and always do what was most pleasing to God.

If she made a vow to stay a virgin, she would always be poor with no one to hunt for her. On Mary’s Feast of the Annunciation, March 25, 1679, Kateri made a vow of perpetual virginity and consecrated herself to Christ.

The priest in the village, Father Tamburini, says, “At about eight in the morning while the priest was saying Mass at which the neophytes received communion, Katharine gave herself to Jesus Christ as a spouse and dedicated her virginity with a vow.”

Kateri lived in the Christian village for three years, often sick, growing weaker. When Holy Week arrived in 1680, the priest came to her house, anointed her, and gave her Communion. People swarmed to her bedside to say goodbye.

Kateri told the women they should go to work in the fields, that she wouldn’t die before they returned. Her friend Mary Theresa said farewell. When the women returned, Kateri died. It was April 17, 1680, on Wednesday of Holy Week, 3 p.m.. Her last words were, “Jesus, I love you.”

Both French settlers and Christian Indians saw Kateri as a saint. Many more Indians became Christians after her death. People made pilgrimages to her grave. She became known as the Lily of the Mohawks, the lily a symbol of virginity.

Today 20 generations later Native Americans celebrate the first saint of the universal Church from among them.