by Vicki Tamoush

It took a split second for my life to change forever. On November 11, at 5:41 p.m., I was the Old Vicki. And at 5:42 I became someone entirely different. The car that hit me was out of control. Neighbors who knew the driver said she has lost custody of her child because of a lifelong drug addiction, several institutionalizations, and multiple suicide attempts.

As her car wove through traffic at double the speed limit, it crossed over two lanes, then the parking lane, and finally sped into the driveway of the parking lot I had just entered.

Actually, I never felt a thing.

The next two years were a series of surgeries on my face and right shoulder and dozens of doctor’s appointments and occupational therapy sessions. Sometimes it seems the accident happened a week ago. But when I see pictures of myself — my old nose, my old mouth, my old shoulder — it seems a lifetime ago, another existence altogether.

Even before I became fully conscious, I began what would become an extensive and troubling dialogue with God. The first night, not knowing exactly what had happened to me or what was to come, I prayed my gratitude for having survived. Later, I would come to wish I hadn’t.

I remember a kind nurse who was among those assigned that night to be sure I would not fall asleep until the extent of my concussion could be determined. She bustled in noisily every five minutes or so, asking if there wasn’t someone she could call for me — a relative? Maybe a friend?

For the life of me, I couldn’t name even one. I could picture my sisters’ faces clearly, but my memory held a blank spot where their names used to be.

Around four in the morning, in an effort to fend off sleep, I asked this nurse how I looked. I knew surgery to reconstruct my face had taken about six hours. She smiled the way angels in ancient icons do and said in a most sincere voice, “You look beautiful, my dear! You are absolutely beautiful!” She was so convincing that I eventually peeked at the mirror she handed me.

My face was held together by several hundred stitches. My cheek and nose had been “manufactured,” as the surgeon put it. My hair was matted with glass and blood, and the bruises had begun to cover my face, working their way over the rest of my body quickly. I could feel that my teeth were loose, and my lips were stiff and unmoving when I tried to form words. This nurse, this icon, this angel, spoke through my pain and horror and convinced me that I apparently was beautiful to everyone but me.

At the urging of my friends, I began keeping a journal, writing clumsily with my left hand. I wrote to applaud myself when I got strong enough to lift a sheet of paper to waist level. I wrote to sort out my feelings of isolation and total dependence on others. And I wrote to chronicle the change in my relationship to God.

There was no time yet for me to challenge God’s Wisdom in allowing me to suffer so. There would be plenty of time later to ask, “Why me?” Right now, I had to concentrate on coping with pain that even morphine couldn’t subdue. I was fighting for my personhood here. I could bawl God out later.

I turned to that most loving image of my childhood, the merciful and beneficent countenance of Mary, to help me conquer this pain. I used anything in my range of vision to count off the succession of Hail Marys and Our Fathers. I recalled all the times in my life I had prayed the rosary and experienced mystical results. What was the nature of this pain that thundered over my most fervent prayer?

A beloved friend just beginning an unsuccessful battle against cancer taught me to use imagery against the pain. He understood how pain can become an entity that threatens to overtake us, and he knew that medication can lead to dependency and a powerlessness of its own.

As I lay in the hospital unaware of the extent of his illness, my dear friend Michael taught me to address the pain, to acknowledge its strength, and to summon a greater strength to overcome it. “This is a job for God,” I thought. Unfortunately, God and I were barely on speaking terms at the time. I had better ask Mary to intercede.

Michael first taught me to focus on the location of the pain, to identify its precise sources. In a soft, hypnotic voice, he described a hot, bright light burning the pain away. As the light burned the pain would fall to the floor, wash away under the bed, the door, and disappear. Lost in his comforting voice, I enjoyed my first pain-free moments since The Accident.

Over the coming months, I modified the image as the pain intensified. I wrote a contract with the pain, allowing it to control me in only the most extreme circumstances. Various clauses of the contract dealt with the method I would use at work, on the bus, or in public if the pain threatened to derail me.

This agreement formalized the reality that pain and I would have to inhabit my body together. It allowed me to pour out my frustration in brief, private tantrums. Perhaps most importantly, the contract affirmed that, as a child of God, I was and always would be stronger than this pain.

When I finally began my occupational therapy, I believed I really would die trying to teach my muscles to work with the hardware embedded in my shoulder. In desperate prayer, while practicing lifting a one-ounce weight, I asked God to give me an image of immutable strength. And just as in my youth, that image came in the form of Mary, Mother of God.

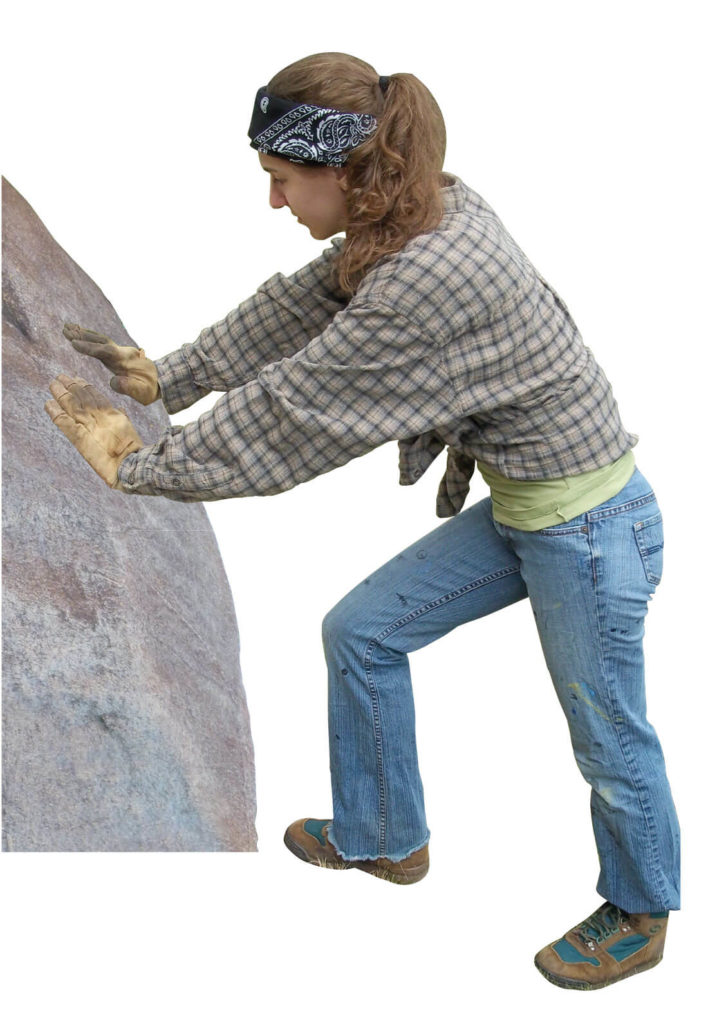

For the tasks of turning over in bed or washing my face, I envisioned a huge boulder of pain standing in my way. Mary would be there, right behind me, cheering me on. “You can do it!” she would call out. “Come on, Vicki! You’re stronger than this pain!” And I would see myself roll away the stone.

Learning to dress myself brought a deeper pain. This pain forced me to change my imagery: Mary stood beside me now, pushing against that huge boulder with her own sweet hands, still encouraging me. “I’m right beside you, child. We can push this boulder away together. I will not leave you. We have more strength that this stubborn rock!” She would sweat with me, cry with me, push with me. Together we would roll away the stone.

I learned to motivate myself from one level to the next in my occupational therapy program. There were plateaus — I couldn’t lift more than nine ounces for ages. Fearing the sharp pangs of pain, I would hesitate to try to exceed my own milestones.

I needed an image for that devastating pain and for the fear that always preceded it. Again, Mary rescued me.

But this was a new, improved Mary. A Mary for the new millenium. The boulder loomed there before us. I stood whimpering in front of it, cradling my limp right arm.

“Don’t worry, Vicki.” She began to pull away her long, flowing robes, revealing her toughest image yet. Under the gown I had always pictured her in, Mary wore overalls and work boots. She pulled thick gloves out of her pocket and rolled up her sleeves as she stomped toward my rock of pain.

“You come stand beside me, child. I’ll move this rock for you.” Her face was pure determination, pure strength. She was a loving mother fighting for her weakened, helpless child. “OK, Vicki. Watch this!”

These days, God and I are back on speaking terms. We pretty much found we couldn’t bear to be apart, seeing how one of us needed the other so much.

I still call on brave Mary to help me roll away the stone. I don’t ask God, “Why me?” And God doesn’t ask me, “Why Mary?”

I still get stuck in my sweater every few days, and I still have trouble combing my hair. But I have an advocate now, one who is willing to don work boots for me. She has combed my hair more than a few times in the past two years.

I have come to terms with my own frailty, which has led me to recognize the importance of living fully in the moment. What happened to me could happen to anyone at any time — even someone I love.

I still fatigue easily. I have lost all but the most rudimentary skills in math and foreign languages. Writing and public speaking don’t come easily to me anymore, and my critical thinking is somewhat impaired.

In putting these words down on paper, I am filled with self-doubt about my ability to express myself. Who would want to read this?

Now that I’ve regained about as much ability as I can expect to, there are more fundamental questions to be answered: How can I do justice and love kindness when I can’t get my sweater on? What good can I possibly do myself and others in a world so unforgiving of someone who labors under an “invisible” obstacle, someone who lacks short-term memory and stumbles over simple words? If I can’t express myself without self-pity, what can anyone learn from my journey? What can I learn?

So far, what I’ve learned is that the journey is all that matters. On this journey, I have learned how to invoke, in prayer, a strength far greater than my own. I am forced to confront my diminished abilities to write and speak publicly by learning to convey information in some other meaningful way.

I have learned that Love is the greatest force in the universe. I have learned now that the Old Vicki lived in perpetual Lent. But the New Vicki has rolled away the stone.

In Mary, the Holy Spirit manifests the Son of the Father, now become the Son of the Virgin. Filled with the Holy Spirit, Mary makes the Word visible in the humility of his flesh. It is to the poor and the first representatives of the gentiles that she makes him known.

Catechism of the Catholic Church #724