by Julie Surma

“I don’t think that’s fair.”

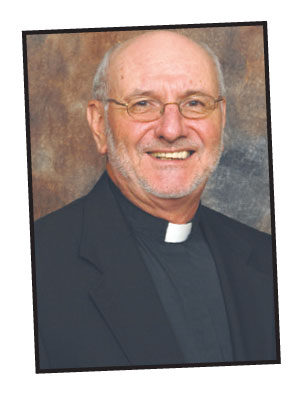

Father John Rausch remembers standing up in class and saying those words. He was a high school student, observing school desegregation in Little Rock, Arkansas. “Seeing the injustice of not letting those young black students into the high school was a decisive, shaping experience for me,” he says.

Fairness still motivates Father Rausch today as a priest working in Appalachia. Here, he stands up for the people and land of Appalachia, seeks justice for its workers and citizens, and works to end and repair damage to the environment.

“As a young man I was looking for adventure,” Father Rausch remembers. “When I saw a brochure with a picture of Glenmary priests riding around in Jeeps, I knew I wanted to be one of them.”

Adventure and hundreds of miles on the road fill a typical week for Father Rausch. “On Monday,” he says, “I’m going to visit death row inmates and say Mass. On Tuesday I’m holding a prayer service on a mountaintop scheduled for mining. On Wednesday I’m giving a talk about environmental sustainability. And on Friday I’m joining a mobilization against the war.”

Father Rausch is one of 60 Glenmary priests and brothers who serve the small towns of Appalachia and the deep South. “Glenmary goes to the small towns, to the forgotten, the neglected, the folks who are not big names. I am imbued with that spirituality,” he says.

“Jesus said, ‘If you throw a party, don’t invite the rich.’ Instead, he said to invite the poor and the lame and the crippled and the blind. Now that’s what my work is about: inviting people to the table. That is my spirituality, inviting people to the table, making sure everybody has enough in order to be more.”

Father Rausch helps others see and listen to the forgotten and neglected people of Appalachia by giving tours of the region. He has named his tour A Pilgrimage to the Holy Land of Appalachia.

On the last tour, Father Rausch introduced the group to McKinley Sumner of Perry County, KY. Mr. Sumner owns about 40 acres of land that has been in his family for three generations. Knowing the coal company was going to mine the land next to his, he sought to protect his property by getting a land surveyor to put up flags around the boundaries.

“But the coal company (International Coal Group, a large company) came in with their bulldozers, went over the boundary, and took 25 feet of his property,” explains Father Rausch. “And he can’t do a darn thing about it. He can get a lawyer, but he has one lawyer and they have ten lawyers. He is left with a legal problem, with legal fees, with their battery of lawyers against his one guy.”

“When I take people on tour,” Father Rausch continues, “We go to people and say, ‘Tell me your story.’ Talking about what has been done to them empowers a person like Mr. Sumner and strengthens his determination to see justice done.”

The tour also highlights the practice of Mountaintop Removal (MTR). People get to see up-close how MTR decimates the environment and damages local homes with little legal remedy.

For coal mining companies MTR is a cheap way to remove coal that is close to the surface. They use blasting and giant earthmovers to strip away the foliage and dirt, sometimes lowering the mountain by 500 feet to expose the coal. The large equipment pushes the dirt off the mountaintop and into the valleys below, burying the headwaters of streams.

The EPA estimates that over 700 miles of streams in Appalachia have been covered. The real cost of this practice includes increased flooding and mudslides, pollution of water supplies, and the loss of the natural beauty of the mountains. Regardless of the ecological costs, America’s insatiable demand for cheap energy continues.

“It’s the most major assault on God’s creation you can imagine,” says Father Rausch. “You can read

about something or even see a film about it, but to get up on a precipice where they are mining 200 feet below is eye-opening. To feel the blast and the earth rumble is jaw-dropping.” The blasts are so powerful that foundations of homes, sometimes two miles away, crack.

The tour also visits a health clinic, where a doctor ministers to people without health insurance. It stops at an eco-village powered by solar panels. Last, the tour visits Sarah’s Place, where women coming out of broken relationships can go to learn marketable skills.

“On a cold, blustery day in December we held a prayer service in an area that had been flooded as a result of MTR,” says Father Rausch. “At the end of the service I gave everyone a handful of wildflower seeds, and said, ‘For the sake of God and community, let’s take back the mountain.’ I fully anticipated them flinging their seeds, getting back into their cars, and heading back down the valley where we had coffee and soup for them. But no, instead, they scattered in all directions, very intentionally planting their seeds, putting one seed here in this cranny, and another one over there. It was a sacred moment. One woman said, ‘I’m sowing my community back.’ What we try to do is replace ugliness with beauty, replace destruction with a hint of the resurrection, to give people hope that another blossom will come.”

For Father Rausch his ministry goes back to fairness. “We can talk about how we are all part of the people of God and that there is the image of God in each person,” he says, “but it just comes down to let’s treat one another right.”

Father Rausch continues, “Ask somebody, are you happy with the way the world is going? If they say no, then you have to say, okay, what’s the alternative? “The gospel is the alternative that invites people to the table, that allows people to have enough so that they can grow to their fullest potential. We can change some of the laws and some of the structures and some of the customs so that everybody is treated fairly.”